Sake - "the drink of the gods" - has evolved over thousands of years and developed particular customs and etiquette as intricate and exciting as any other beverage in the world. Primarily associated with Japan, it holds a proud history, fascinating traditions, and clean yet complex flavor profiles. So, why do most Americans seem to know so little about it?

Although it was discovered in China as early as 4800 B.C., sake quietly remained in Asia, and principally Japan, for most of its life. It was only in the 1880s that sake made its global debut in the suitcases of Japanese immigrants traveling to Hawaii as laborers on the sugar plantations. Aloha, exotic tasty beverage. With the rise of Japanese culture and influence abroad, sake has experienced rising popularity in the West, especially among youth, who are more prone to fermented experimentation. But despite the recent dabbling, sake's character-laden labels and foreign terminology can still make one feel a bit lost and intimidated. In a series of posts, I attempt to assuage those feelings, and get you drinking with confidence. Kanpai!

Originally devised to measure rice in feudal Japan, today, the masu is most frequently associated with drinking sake.

Sake contains 400 flavor components - twice that of wine - and comes in an array of styles, from sweet to bone dry, clear to milky white. It often displays fruit, floral, earth, spice and honeyed flavors and aromas. The similarities in style, aromas and flavors often result in the mischaracterization of sake as a “rice wine.” It is in fact not a wine. Nor is it a beer. Sake’s unique ingredients and brewing methods put it in a category of its own. With a beverage this delicate and delicious, it is worth further exploration.

The Building Blocks of Sake.

Sake is a simple beverage with only a handful of components. With a mere four primary ingredients, quality of each is paramount.

1. Rice.

Not surprisingly, rice is the foundational ingredient for sake. But not all rice is created equal. Two considerations.

First, table rice is not equivalent to sake rice. For hundreds of years, sake rice varietals have undergone genetic manipulation and selective breeding for the precise purpose of brewing sake. Japanese growers have become experts at identifying and enhancing the chemical compounds and makeup that constitute certain desirable flavor profiles. Compared to table rice, these rice varietals are larger in size, contain fewer fats and proteins, and more starch that is concentrated in the center of the grain. Table rice, bad. Sake rice, good (for making sake, of course.) This is not to say, however, that all sake is made with sake rice. Some lower-grade sakes utilize less expensive table rice varietals. Amongst the premium-grade sakes, however, sake rice is indispensable.

Second, sake rice runs along a quality continuum, with yamadanishiki emerging as the gold standard. Rice can be a source of pride for many villages, and certain prefectures (the term for a sake region or appellation) in Japan, such as Hyogo Prefecture (with its storied yamadanishiki), emphasize its superiority of sake rice vis-à-vis other varietals.

2. Water.

Sake is about 80 percent water, so it may seem obvious that better water equals better sake. But its only water, right? Wrong. Premium water contains higher levels of potassium, magnesium and phosphoric acid (which aid in the propagation of yeast and development of koji), while extrapolating all traces of iron. Iron accelerates the aging process, and can create unpleasant aromas and flavors. Today, water is less significant regionally because it can be easily transported, but certain prefectures still boast about their excellent quality water.

80 percent water; 100 percent delicious.

3. Koji.

Koji is central to the brewing process. Koji is a mold that is added to sake rice to break the starch down into glucose, inducing yeast to breed. This influences the character and style of the final product. Koji was a welcomed innovation from the old school chew-and-spit method, known as kuchikami no sake. In this tradition, villagers (often young virgin women, believed to be more pure than the other country yokels) would pass the time chewing on rice grains and spitting them into a communal cask. Enzymes in the saliva would facilitate the conversion of rice starches into sugar, allowing fermentation to occur. I’ll take the koji, thanks.

Without koji (or saliva, I suppose), fermentation could not occur. Without fermentation, no alcohol. No alcohol means no fun.

4. Yeast.

Finally, yeast. Yeast is a microscopic unicellular fungi that feeds on sugars and simple carbohydrates. These yeast cells are critical to the fermentation process, as they break sugar down into alcohol and carbon dioxide. Although yeast occurs in the wild, it is most often cultivated in labs for brewing purposes in order to develop a complex and harmonious array of aromas and flavors, as well as favorable rates of fermentation, temperature tolerance, and other factors. Commercial yeast strains are available for purchase, but some brewmasters (called “tōji”) prefer to develop their own proprietary yeast starter to afford a truly unique flavor profile for that particular brewery.

So, how do these four basic elements become transformed into an enticing beverage served in mini sake cups (called “ochoko”)? And, please, can I use a slightly larger ochoko?

The Sake Brewing Summation.

During any fermentation process, sugar is converted to alcohol. Sugar plus yeast yields ethyl alcohol, carbon dioxide, and heat. Wine is capable of fermenting without human assistance, as wild yeast can naturally break down sugars from the fruit. Sake and beer, on the other hand, begin with grains, not fruit. Therein lies the problem: no sugar. For fermentation to occur, the starch in the grain must first be converted to glucose (a process called saccharification), before the sugar is converted to alcohol (fermentation).

Mill Me, Baby, One More Time.

Sake brewing commences with rice polishing, or milling. Nearly all rice is polished. That white rice you had for dinner ... it wasn’t naturally white (at least by outward appearance). Table rice, often brown in color, is customarily polished by 10-12 percent, removing the husk, bran and germ, and leaving approximately 90 percent of usable rice grain that now appears white. A similar process occurs with sake rice. Milling removes the outer layers of the sake rice grain, which include fats, proteins, minerals, vitamins, and other compounds that distort flavor, to reach the more concentrated inner layers of starch (ultimately destined for alcohol production). Generally, the more the rice is milled, the higher the quality and the more expensive the sake. Sake rice can be milled by 40 percent or more, and the percentage to which the rice is milled is called “seimaibuai.”

The Hangover Curtailment Hypothesis.

Milling is said to provide a side benefit, felt (or not felt) mostly the next morning. Congeners are minor compounds that occur naturally in alcoholic beverages as a byproduct of the mash fermentation process. These impurities are thought to cause hangovers. In sake rice, congeners primarily take the form of proteins and fatty acids concentrated in the outer portion of the rice grain. Because sake brewing utilizes polished rice that is a mere 30-50 percent of its original size, these impurities are mostly eliminated. As they say in Japan, you know good sake the next morning. Yes, bartender, I will have another.

Too good to be true? Perhaps. Alcohol and dehydration are the primary culprits for a hangover, with congeners playing a relatively small role. While reduction of congeners certainly helps, it is not a failsafe strategy for avoiding hangover. Keep the water coming. Of course, congeners are considered unhealthy, and any reduction is welcomed. So when your spouse questions the necessity of that expensive bottle of daiginjo, remember that your health is of preeminent concern.

After polishing, rice is washed to remove all residual flour, and is then soaked and steamed.

Koji Time: The Fermentation Catalyst.

A portion of each batch of steamed rice has the honor of koji duty. The koji spores, appearing as a dark, fine powder, are applied to steamed rice that is spread out on broad, flat trays in a temperature- and humidity-controlled room. Workers spread the mold on top and then massage the koji powder into the rice. Mmm, koji rice receives royal treatment. The enzymes in the mold break down the rice’s starch molecules and convert them into sugar. The final product looks like frosted rice grains, with a subtle aroma of sweet chestnuts.

The three amigos. Sake set consisting of the traditional masu, small ochoko, and serving tokkuri.

M*A*S*H.

The steamed rice, koji, water, and a yeast starter (comprised of yeast, water, rice and koji-rice) are then added to a large tank to commence the fermentation process. This combination is referred to as the "moromi," or the main mash. The ingredients are gradually added in three successive stages over four days, roughly doubling the size of the batch in each stage. This unique three-step brewing process allows brewers to monitor numerous factors (e.g., temperature, starch, active yeast cells, alcohol, etc.) and make adjustments in real time for greater precision.

Once the tank is full and all components have been added in the desired amounts, the batch is left to ferment, usually for between 18 and 32 days, in a large, open, cylindrical tank. During this time, the koji continues to break down rice starches into sugars, and simultaneously yeast is converting those sugars to alcohol and carbon dioxide. This “multiple fermentation” stage is unique to the sake brewing process. Throughout this fermentation period, the tōji (brewmaster) can make modifications to ensure that the final product will result in a certain desired style (e.g., sweet, dry, rich, light, etc.).

During or at the conclusion of fermentation, the tōji can add distilled alcohol (a technique adopted during World War II as a strategy to conserve rice), but the distilled alcohol will kill off the remaining yeasts and stop the fermentation process.

The sake is then pressed and filtered, a dual process that removes the unfermented rice solids from the liquid and strips out unwanted flavors, colors and other elements.

Once the sake is pressed and filtered, the next step is often (but not always) pasteurization. Sake is pumped through a pipe submerged in hot water, heating the sake to around 150 degrees fahrenheit. This extreme heat kills any remaining enzymes, bacteria and yeast to make the sake shelf stable without refrigeration.

Finally, the sake is ready to be stored. Water is usually added to dilute the sake to an alcohol level of around 15 percent (down from 18-22 percent). Most sake is aged for three to six months before bottling and shipping, allowing the flavor profile to mature. Unlike wine, however, sake is not usually aged for long periods and should not be purchased if more than 12 months old, and ideally less than 6 months old. The label will state the date of bottling, so be sure to check before procuring a bottle.

Categories of Sake: You Can Judge a Book By It's Cover.

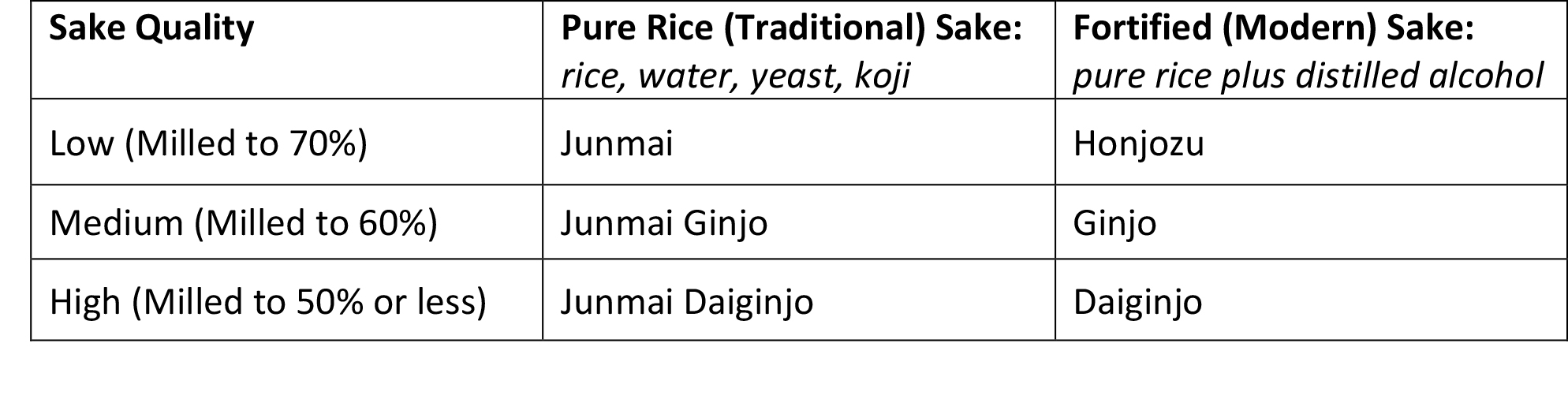

As discussed above, sake quality depends on the amount that each grain of rice has been milled. A sake’s designation on the bottle (e.g., Junmai, Honjozo, etc.) will indicate its quality. The table below summarizes:

These general categories will help you to navigate the sake aisle with moderate but consistent success. To go to the next level, a few supplemental terms will be necessary:

1. Genshu.

Genshu is an undiluted sake that has no water added before bottling. This sake packs a punch, often with alcohol in the low 20 percent range.

2. Nigori.

Nigori is unfiltered or “cloudy” sake that is often quite sweet. Unlike most sake, nigori sake is not pressed. Instead, it is strained through a mesh screen that allows rice particles from the fermentation mash to pass through. With these additional particles, the sake is milky white and opaque. Shake well.

3. Nama.

Nama is a type of sake that has not been pasteurized, and therefore requires refrigeration. This style is often released in the springtime, and creates fresh, vibrant flavors. It's one of my personal favorites.

4. Tokubetsu.

Tokubetsu is a special designation of junmai sake that is milled to 65 percent - between that of normal junmai and junmai ginjo.

Mastering Food and Sake Pairings.

Even the briefest sojourn to the local sushi counter will confirm the preeminent pairing of sake and sushi. Unfortunately, this is where many will naively choose to conclude their sake pairing experimentation. A tragic tale.

Sushi and sake are a classic pairing, but an adventurous spirit will be rewarded with boundless opportunity.

Although often subtle, sake has extraordinary flavors and aromas, and can range from light and delicate to full-bodied with umami notes. With such flavor diversity comes a panoply of pairing potential.

Thai? Vietnamese? Korean? Mexican? Italian? French? No problem. There is a sake for that. In Part II, we will explore several food and sake pairings from a variety of cuisines. I will elaborate on sake categories, labels, flavor profiles, and characteristics, and discuss how to specifically pair certain sakes with non-traditional cuisines. Stay tuned.

Kanpai!